Douglas Gordon (Part 2): The troubles with Typhoons

January 9, 2019 by Stephen J. Thorne

(Click to enlarge) Douglas Gordon, 95, with his RCAF identification card, issued when he was 19.

STEPHEN J. THORNE/LEGION MAGAZINE

If the Germans didn’t get you, the Typhoon just might.

Flying Officer Douglas Gordon knew it only too well. Between June and August 1944, 19 Allied squadrons—his own among them—lost hundreds of the hulking aircraft and 150 pilots, many of them due to engine or structural failure.

“She was a monster; she was just a real miserable aircraft,” said Gordon, a 95-year-old native of Lachute, Que., who survived 99 combat missions at the stick of the Hawker-built plane. He flew multiple sorties on D-Day and into the Falaise Gap with 440 (City of Ottawa) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force.

A Hawker Typhoon. Gordon called the plane “a monster. . .just a real miserable aircraft.”

COURTESY OF DOUGLAS GORDON

The Typhoon was a contrarian of the rudest sort. To start with, its propeller turned counter-clockwise instead of clockwise like most aircraft. Three metres off the ground, its cockpit was crammed with some 85 instruments, switches and levers—“all sorts of crap and corruption,” as Gordon put it.

It proved a rude awakening after flying Hawker Hurricanes. “You got the surprise of your life when you got ahold of one of those things,” recalled Gordon, who ran one into the long grass off the runway on his first takeoff: “The sonofabitch, you couldn’t control it. I think I was 20 miles away before I got the wheels up, even.”

It had a surly disposition. Designed initially as an interceptor, the Typhoon engine had a disconcerting tendency to quit at the most inopportune moments. “The aircraft had a lot of problems which would show up later on.”

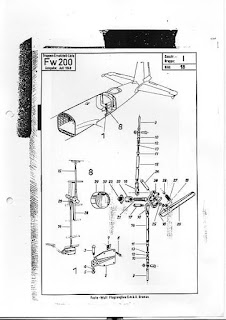

Not the least among the Typhoon’s issues were its similarities in appearance to the aircraft it was initially designed to stop, the Focke-Wulf Fw-190. From some angles, the Typhoon’s profile resembled that of its main foe, precipitating several friendly-fire incidents involving Allied anti-aircraft units and other fighters.

Early versions, the Typhoon Type 1A, were powered by 2,000-horsepower, 24-cylinder Napier Sabre or Rolls-Royce engines. But both the 1A and its successor, the 1B, were plagued by design and technical problems. Gordon flew both.

Two armourers of Gordon’s 440 Squadron trudge through the mud of the B78 airfield near Eindhoven, Netherlands, to re-arm a Hawker Typhoon fighter-bomber in 1944.

SAIDMAN/IWM/CL1598

The Typhoon could be hard to start, especially on cold days, and it had a poor rate of climb—not great characteristics for an interceptor. The cockpit was hot and armour plating inhibited visibility, but those could be the least of a “Tiffy” pilot’s worries.

It blew dangerous amounts of carbon monoxide into the cockpit. The problem was never completely resolved and, throughout its service, it was standard procedure for Typhoon pilots to use oxygen from engine start-up to shutdown.

“You’d put the oxygen on for 10,000 feet on the dial before take-off,” recalled Gordon, a salty-tongued plain talker who pulled no punches during an extensive interview with Legion Magazine. “Carbon monoxide was a big problem.

“Pilots just went over and turned down into the ground. [Crash investigators] figured they’d lost consciousness.”

Gordon (front, far right) with 440 Squadron mates at RAF Station Hurn in Dorset in June 1944.

COURTESY OF DOUGLAS GORDON

In the rush to counter German development of the Fw-190, early Typhoons were first flown on Feb. 24, 1940, as replacements to the slower Hurricane—Gordon’s favourite aircraft. There was no time for proper trials. Test pilots died even as it entered service.

During the plane’s first nine months of combat operations, more Typhoon pilots were killed due to engine and structural failure than by enemy action.

Oil coolers failed, forcing engines to cut out on landing. Gordon said the motor would restart and shut down multiple times before dying altogether.

“There was a flight of four Typhoons that had taken off from this airfield and all of a sudden I heard this familiar sound.

“Aaaaa-ump! Aaaaa-UMP! And every time it cut, it cut closer. It would go aaaaa-cut, aaa and then all of a sudden the two cuts would come like that. And then ‘Oh fuck, there’s another one.’ Anyway, that was the Typhoon. Very unreliable.”

Gordon watched as the plane left the formation and started descending.

“He was coming in nice, and he came right across this field. He was over quite a piece from where we were. A perfect landing. Wheels up. The engine was dead.

“All of a sudden he somersaulted, end over end. Why? Because the army had gone across that field and built themselves a road and he hit the side of that road.

“They got to him. The aircraft had buckled, the tail was sticking up in the air. And he was in the middle of that, laced into his cockpit with all of his equipment on. He was dead, the poor bastard.”

Sometimes the engine sleeve jammed and the cylinder would explode.

The aircraft was also prone to mid-air structural failures at the joints between the forward and rear fuselage.

In steep dives, the tail would vibrate violently. The whole tail section could break away. Gordon said they wrapped the rear fuselage with reinforcing belts.

(Click to enlarge photos) Pages from Douglas Gordon’s wartime logbook, showing losses and mission details.

STEPHEN J. THORNE/LEGION MAGAZINE

In his logbook, he made notes of incidents big and small.

On June 10, 1944: “Bernier—engine cut out on takeoff. Cat. (E) crash [a write-off].”

On July 16: “WO McConvey blew up on takeoff.”

Early Typhoons had three-bladed props; later ones four.

“The three blades shook the livin’ shit out of ya,” said Gordon, who flew a dozen different aircraft types during the war, including P-40s, Hurricanes and Spitfires.

“They told you that you couldn’t make a woman pregnant flying a Typhoon. It was a joke.” (Gordon himself fathered three boys).

Things did not improve much with the 1A’s successor, the Typhoon 1B. The British government ordered 1,000 anyway and ultimately began using the plane, and its bigger engine, in what proved to be a more suitable role—as a fighter-bomber.

Issues persisted, however.

Now armed with four 20-millimetre cannons and some carrying eight 60-pound rockets, the Typhoon packed formidable hitting power. Equipped with the newer 2,250-horsepower engine, it was faster and had more range but there was a problem with the cannons—they would explode.

“When we were in France, they had trouble with aircraft blowing up in mid-air,” said Gordon. “This one guy fired his cannons off in a dive and the aircraft blew up.

“He got out. His name was Dougie Stultz, a Maritimer. He got burned quite a bit.”

‘Babs VI,’ a Typhoon of No. 174 Squadron, RAF, coded XP-K, was photographed at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands on Feb. 9, 1945, the day after it was written off following a forced landing caused by engine failure.

IWM/MH27462

“So they grounded all the aircraft and they checked all the electrical connections and they found five of them that were no good and the rest were all good. I was on duty that day. So they said ‘will you take one up and take it out to sea and fire the cannon to see whether or not the aircraft blows up?’ I said ‘you’re crazy.’”

Nevertheless, he did it. “When I went to fire the cannon, I’m tellin’ ya, I was scared.”

Three weeks after D-Day, 440 Squadron moved to northern France, where sand and dust caused even more problems.

The Typhoon had a big air scoop under the cowling and the sleeve-valve engine turned out to be particularly vulnerable to the conditions at their new location.

“That [scoop] was a goddamn dust collector. They didn’t have a filter on it. It would suck sand into it in France and when the sand got into it, you weren’t airborne for too long. They said the dust was as good [fine] as emery dust.”

When it wasn’t quitting from the dust, the engine was constantly spitting oil.

“I remember my brown jacket,” said Gordon, “the left shoulder would be black from the oil coming out of the engine. The windscreen would get black.

“You had to land with the coupe top [canopy] open because if something happened, if you rolled or something, it would be nice to get out. You rolled it back when you took off and, for the same reason, you had it open when you landed.

“The result was, the oil would hit the windscreen and it would hit you when you were landing and taking off. Sometimes, it was really bad. We’re talking visibility at just about zero.”

Spitfires encountered similar problems in North Africa. A custom-designed filter made by the Vokes company in Ireland solved them.

Gordon’s hand-drawn diagram of Typhoon attack patterns.

STEPHEN J. THORNE/LEGION MAGAZINE

For the 156.15 hours that Gordon flew the Typhoon—his last sortie before he moved on to Spitfires was Nov. 11, 1944—her engine had a tendency to miss.

Once, he was in a formation of nine aircraft, flying wing on the squadron leader, just behind and beneath him in what was known as the No. 2 position.

“All of sudden I notice I’m starting to slide underneath him. I cut back. Then you’re affecting the guy behind you and all the guys on both sides. I get back in position and, first thing you know, my propeller is right underneath his tail.

“Finally, I just pushed the stick and went into a dive. His Typhoon was missing; the engine was skipping on him and missing and missing. And he lost power. He was sinking. That’s what the Typhoon did. It was very unreliable.”

The Typhoon finished the war but the process of replacing it had already begun by the time the fighting stopped. Its successor, the Tempest, was a better plane, say pilots, but, like most aircraft, it too had its growing pains.

By war’s end, some 3,300 Typhoons had been built, and 26 squadrons of the 2nd Tactical Air Force had flown the beast. The bulk of the surviving Typhoons were destroyed when it was over.

A Douglas Dakota of RAF Transport Command (background) lands at snow-covered B78 near Eindhoven, Netherlands, as ground crew inspect Hawker Typhoon Mark IB, MN659 I8-E, of Gordon’s No. 440 Squadron RCAF, which suffered a collapsed undercarriage on landing after a sortie. Gordon flew this aircraft numerous times.

RAF/IWM/CL3810

Only one complete aircraft exists today. It was originally on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., then presented to the RAF Museum in Hendon, North London, in exchange for a Hawker Hurricane.

The aircraft was recently returned to London after it was on loan to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa for most of the past four years.

“I never really trusted the Typhoon,” said Gordon. “You couldn’t. You could trust the Harvard. I trusted the Spit. Not the Typhoon. You looked at Typhoon pilots, they weren’t really happy.”